Welcome to “Handmade Hero Notes”, the book where we follow the footsteps of Handmade Hero in making the complete game from scratch, with no external libraries. If you'd like to follow along, preorder the game on handmadehero.org, and you will receive access to the GitHub repository, containing complete source code (tagged day-by-day) as well as a variety of other useful resources.

(Top)

0.1 Our Journey So Far

1 About Software Architecture

1.1 Software Architecture vs. Real Architecture

1.2 Pick the Right Term

1.3 Compression-Oriented Programming and Urban Planning

1.4 Why Do We Need Architecture

1.4.1 Reuse

1.4.2 Division of Labor

1.4.3 Mental Clarity

1.5 Measurements of Success

1.6 Game Architecture

1.7 Logic Flow

1.8 Data Flow

2 Recap

3 Navigation

Our Journey So Far

In the past 25 days, we've been working on the platform layer. We tried to get it done first to avoid getting tangled in the platform code moving forward. Looking back, we succeeded.

Of course, there would be tons of things to clean up in the prototyping layer we've written so far. But, for the moment, it's plenty good for our purposes. Since we can already say that we'll eventually revisit our platform layer to complete it, we can call it a day there and move on. Sure, there will be other moments where we'll need to come back and add a feature here and there. Those will be dictated by how our project evolves.

While we had some moments of fun, up until now, we were mostly trying to get something out of the system that we knew it could provide. In other words, we were interfacing with the code that some other programmers wrote. It might not be a terrific piece of code, accurately documented, or indeed created with your specific needs in mind. We also might not know what's happening under the hood. It often boiled down to “We call Windows, and it does what it does. Hopefully, it's always consistent in bringing back the results we expect.”

This type of work, while necessary, is a lot less satisfying.

Today is the first day when we will be making the game part of Handmade Hero. We'll be programming in quite a different manner than what we've been doing so far. It will be exciting, full of mysteries and puzzles to crack, and we don't have to think about the complexities of the underlying platforms. Even with the rendering system: the first version of the renderer will be written by ourselves, without leaving it to the graphics card driver to do all the magic. We will know every last pixel on the screen, why it got there, why it looks like it does, how we computed it, and so on.

After all, we are writing everything from scratch. And we're doing it for several reasons. One, it's a lot of fun, and hopefully, now that we're in our code territory with everything under our control, you'll see that. On the other hand, working on such a project is very educational. One of the big reasons why this project exists is precisely to show how every last thing works. It's so interesting, and all of this is often lost when working in a prefabbed game engine. You don't get to see everything that's going on, and it's useful for everyone who works on the game programming to do the whole pipeline at least once.

About Software Architecture

Today we'll mostly do theory. Specifically, we'll start defining our game's architecture.

The term “Software Architecture” encompasses many practices. Some good that you should adopt into your work, but some quite harmful that you should avoid. So before we go into the actual architecture, we should talk about what we intend for it. It's important to discuss why we call things the way we call them and what stands behind them.

Software Architecture vs. Real Architecture

The term is, of course, coming from the building construction. The architects, the people designing said buildings, would draw detailed charts containing all the information on the building: wall thickness, location, even material, electrics, water loops, and so on. These “blueprints” would be printed on rolls of traditionally blue paper, hence the name. Of course, for large constructions, one single sheet might not contain all the information, but the whole complex of the blueprints would.

So the architects make the blueprints and give them to the contractors: carpenters, electricians, and other people who would take them and do the actual building. After all, the construction process involves a lot of stuff: nail things together, there's some masonry involved, and the cranes haul other things around... It's always a complex project.

A blueprint (or the collection of blueprints) is the document containing the information on the whole building. If I hand two contractors the same blueprints, leaving the quality of their work aside, the end building will be the same. It's not like one would build a long rectangular structure and the other a sphere dome.

Now here lies a big difference when it comes down to software. Some who talk about software architecture take the above metaphor literally. The result of the software architect's work should be an ever-encompassing document describing every aspect of the program (using, say, a UML diagram).

These methodologies try to define the program definition or the program spec. Whichever programmer comes to work on such a “blueprint” would produce precisely the same program. You might encounter such a methodology in a hardcore object-oriented school of thought. There would be a lot of preplanning, diagram drawing, and so on.

Such an approach is not only the opposite of exciting. Programs are very complex, with many moving parts involved. If you can make a blueprint specifying the program to a significant degree of detail, leaving no room for the variability of what comes out as a result... You essentially have just written the program, just as a diagram. A sufficiently advanced programming language might as well interpret it and produce sufficient machine code from that product.

A couple of decades ago, building the program in this way was the bleeding edge of industry thought. Luckily, many people nowadays mostly understand the concerns above. Using an approach like this results in a lot of up-front work with not enough payoff. Even further than that, anecdotally, products designed upfront often fail to produce good quality programs in a reasonable amount of time. If such a tool is used, it's used sparsely or to provide a higher-level overview.

Pick the Right Term

Having said all this, “Software Architecture” is coming out to be a little of a misnomer. If we want to go with the construction world metaphors, a more precise term would be “Software Urban Planners,” or simply designers.

Let's look at the big picture.

In this metaphor, what people call “software architecture” would be the role of the designer. The actual “architects” would be the programmers, people making the “blueprints,” code for the compilers to execute upon.

That sounds good, but why do we even make a distinction between architects and programmers?

Once defined, real-world architects rarely make significant alterations to their buildings during the construction process. It's very costly. It's not because it's better or easier to have a preplanned project before you start building it. It would be very convenient if the architect, say, designed and erected a lobby, and then went about saying: “huh, it's not hitting the sun quite right! Let's tear it down and rotate it a bit.” They would love to do that, but it takes too much money and time to build things in the real world.

Thus, the act of preplanning the architecture of a building takes place entirely because of real-world constraints. In the programming world, the structure of things is more malleable. As an architect who'd want to constantly mutate their building, programmers can constantly mutate the shape of their programs.

Compression-Oriented Programming and Urban Planning

We already talked a bit about compression-oriented programming (on Day 8 and Day 19). We first splat some functionality out the way it comes to us. Then, when we see that some concepts start taking shape, we abstract them out as necessary. It's a very fluid system, and if one could build a building this way, one probably would.

Mutating code is not complicated unless you factor it into pieces prematurely.

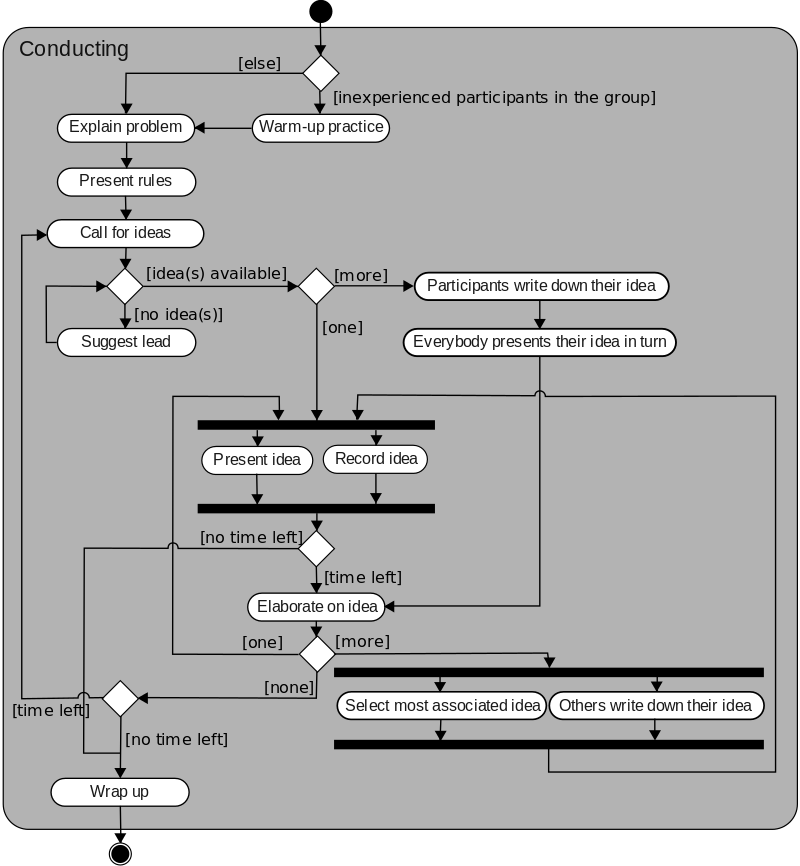

If you look at someone talking about software architecture, they don't draw things resembling blueprints. They don't sketch out the structure of the program as the CPU would execute it. They would sketch out something like this:

This is where urban planners and software architecture meets. In urban planning, you're not talking about a specific building. An urban planner thinks about how a city works: zoning, height limits, etc. And if you look at the Figure above, what you see are... street maps. They talk about the “traffic flow,” their relationship with each other, and their responsibilities. That's it.

In our opinion, doing the above is both a natural and the right thing to do. Therefore, when we talk about software architecture, we don't talk about real-world architecture but urban planning. The high-level zoning and traffic strategy for our program, if you will. Thinking through roughly where each thing has to be, what it should do, how much it will cost us, and how efficient it should be to move items around.

Why Do We Need Architecture

In software architecture, all the strategies that we develop essentially boil down to efficient code separation. Here the urban planning metaphor comes up nicely. We draw the property map by first defining where each thing is going to live. We make sure they don't overlap and define the traffic patterns. Crucially, we explain what each area is trying to achieve.

Software architecture is about defining boundaries. We need those for Reuse, Division of Labor, and Mental Clarity.

Reuse

On Handmade Hero, our platform layer currently doesn't know a whole lot about the game whatsoever. We've done a thorough job setting boundaries. Therefore, turning it into a reusable platform layer wouldn't take much work if we wanted to.

Division of Labor

In the case of Handmade Hero, we are all writing the game by ourselves, so it's not a problem here. But let's say we have a small team of two to four programmers (or, worst-case scenario, an operative system project with 500 people on it). We will need to have different people working on various components so that communication requirements wouldn't overwhelm the entire project. If each of us works on code we want at any time we want, eventually, you'd run into all sorts of problems.

Mental Clarity

When you tackle large programs, regardless of their size, most programmers will face the challenge of keeping the entire thing in their heads. As your programs grow larger and larger, your architecture becomes about keeping things separate, so you don't have to consider them at once.

Imagine the other way around: if everything is interconnected, then any change to the program would have consequences for the rest of it. That would be an \(\O(n^2)\) problem for your brain. (We didn't discuss the Big O notation yet but suffice to say, it's becoming exponentially more difficult.) That's a lot of brainpower. It would be much simpler put labels on some pieces of code and worry only about connecting those.

Measurements of Success

Now that we defined the objective, and the “Why” we adopt this approach, let's briefly talk about how we would measure our goals being met. Programming, in general, is a hard thing to quantify, but we can use specific hints left along the way.

When a game executes, things happen: entities update their position, the sound is written to some buffers, the image is written to others, etc. We can draw boundaries between these various “components” as we defined above. However, the sequence in which the various components are executed is not necessarily arbitrary.

Let's make a simple example. Say, we have two systems, each with a well-defined boundary: a physics system and a renderer. The latter is responsible for drawing the game on the screen, while the former moves the things in the game. If that's the case, we can't just run these two components randomly. We can only Render the image on screen after the Physics system has finished placing the things around the world.

This is known as temporal coupling: one thing must always be executed before the other, therefore two (or more!) components effectively become one.

If you look at the two systems outlined above, you'll also notice that one system produces useful data for another. The way this data is laid out in structs can have various implications, therefore you can think of it as “layout” coupling. For instance, there might be a performance concern because the systems would prefer to use different parts of the data: the physics system would care about the object's position and, say, velocity, while the renderer would look at the position and size.

So how would we approach this problem? Do we translate the data? Do we accept that one system is slower? Do we make a compromised layout that is “good enough” for both? These “Layout Coupling” issues are also things we can address.

There're other “couplings” we can consider. For instance, we can build our program differently depending on whether or not it uses a multithreading system of some kind, how the memory is used, if it makes wide calculations on a single core (SIMD etc.), and so on. This can be summed up as “ideological” coupling.

Finally, we can measure a program's “fluidity”. Fluidity falls in the category “you know it when you see it”. How simple is it to bring big changes to the architecture, without having to rewrite it all from scratch? Especially during the first phases of development, this aspect can be quite important indeed! A fluid system would allow these changes with relative ease.

Game Architecture

Let's talk about game architecture, and more specifically, the game architecture we chose for Handmade Hero. Up until now, we were laying out the foundation, our platform layer, for the rest of the game. But in doing so, we made specific choices that, up until now, weren't explained in depth. You can say that we cheated a bit and skipped ahead, as we have a good idea of how a good prototyping layer and a good platform layer should be.

At the very bottom of our game, we have our Win32, and we'll have our OpenGL or Direct3D later down the line: things underneath us that we can't do anything about. Above it lies a platform layer that we have a skeleton for. It needs more work before it's production-ready, but we already have a good idea of how it will look.

We then have Game Update And Render (or GUAR for short) and Game Get Sound Samples (GGSS). These things call into the Game.

Until now, we didn't even pretend that we didn't know what we were doing. It wasn't all that interesting. With the Game, however, we will explore the path as we go, and discuss the different principles as we go.

Logic Flow

Let's try and dive into this “Game”. What we will need for it? Well, as the entry points we have the GUAR and GGSS.

Game Update and Render is our first entry point.

- We wait for a call from the system containing information about

t, how much time we need to advance our world by. This means:- Processing user input. We must do it as close to world update as possible, to avoid introducing input lag.

- Running a physics simulation of the world.

- We render the world to bitmap.

The Game Get Sound Samples function doesn't even need to be considered as a separate function call, just as an extension of GUAR. Maybe eventually we'll be able to tie the two in a single call. This stage boils down to:

- Output the sound samples.

Update and Render are often separate functions that many games process at different moments. It's an ideological choice, it makes sense in terms of the desired set of operations. But even if these two functions are processed one after the other, a boundary between the two is established. We won't be doing this. Drawing a boundary at the architectural level between the two precludes the road to some potential optimizations, where it would be more cache-friendly to do the physics update and render call in one fell swoop. Again, consider this “render” step more as a “render prep”, since the rendering itself is delegated to the GPU these days. We'll do rendering ourselves, for a short while, but even then we'll use the same methods a GPU would function.

Our boundaries will therefore look like this:

Data Flow

We need also to think about how the data would flow. Here, there're two popular schools of thought: “Loading screen” and “Streaming”.

In the “Loading Screen” architecture, the game waits for a specific event (e.g. change of level) where it loads all the information related to that level. The user in the meantime gets to watch a little spinning thing and maybe an interesting fact about the game world. During that time the resources are being loaded from somewhere: a CD/DVD, Hard disk, or even the network. These are the resources used to prepare video and audio outputs, as well as those strictly gameplay-related: level maps, monster data, etc.

Ultimately, one chooses the Loading Screen architecture because there is not a lot of real architecture going on. While the loading happens, nothing else is. There's no input processing, sound usually dies down, the physics system sleeps, etc.

On the other hand, when you are “Streaming”, all the resources are procured by the game while it's running. It's a process that happens in the background, usually on another thread. This results in another architectural boundary. There's a back-and-forth communication going on between the loading system and the rest of the game to ensure that the required assets are ready to be used.

It's important to get this boundary right. Many projects do it wrong. There are considerations like “do we want to use immediate mode or retained mode?”. But that is something that we can look into when we will get to. We don't want to get bogged down in too much planning. Time to get our hands dirty, but we'll do it next time.

Recap

Wow, that was a whole lot of theory! And not enough actual code. But it's oh so important to have a good overview of the voyage we are about to embark on before we do so.

Navigation

Up Next: Day 25. Finishing the Win32 Prototyping Layer

Up Next: Day 27. Exploration-based Architecture

- Fluidity

- Software Architecture

- Program Spec

- Temporal Coupling

- Resource Streaming